According to a press report on Friday, California winemakers have also complained to Trump about an Australian tax on wine sales, calling it “unfair”.

Since the return to power of US President Donald Trump, tariffs have barely left the front pages.

It should be emphasised that these measures have a legitimate role to play in our trading systems.

What are non-tariff measures?

However, the existence of so many of these measures in the agricultural and food sectors may also be a political issue. Agricultural lobby groups are powerful in many countries and continually push for protection from imports. In this case, the measures can be viewed as barriers.

However, we do have to be careful in interpreting these results.

Non-tariff measures can be separated into categories, such as sanitary and phytosanitary (food safety and plant/animal health-related), technical barriers to trade (food standards, labelling, and so on) and quantitative restrictions (such as quotas).

The report says these non-tariff measures are equivalent to Australian agricultural exporters facing a tariff of 19%.

Australia’s food security measures relating to beef are being explicitly called out by the US farm lobby. A US beef trade organisation called the Australia-US free trade agreement “by far the most lopsided and unfair trading deal” for its farmers.

Australia is in the crosshairs of Trump’s trade war. On April 2 the United States is set to implement a new wave of tariffs under its Fair and Reciprocal Trade Plan. These will target both tariffs and non-tariff measures.

How do they become a barrier to trade?

There is no doubt there are significant gains to be had from disentangling genuine measures that protect human, plant and animal health from those that hinder trade purely to protect inefficient domestic producers or favour certain countries over others. Once this is done, work can be undertaken to reduce the unjustified barriers.

- unclear or unevenly applied

- more trade-restrictive than necessary to meet their stated objective, or

- introduced to provide an unfair advantage to domestic industries.

An increase in justified measures is very different from an increase in unjustified measures.

Why agriculture is so exposed

The report also highlights the costs of the measures, but does not consider the benefits. The example of foot and mouth shows that the benefits of non-tariff measures can be very large.

While the on-off-on tariff sagas have dominated the headlines, a paper released this week by the government’s Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) has highlighted other barriers. These non-tariff measures could actually be having a greater impact in terms of preventing trade.

Both justified and unjustified measures can work to prevent free trade. But the report also shows how non-trade measures can facilitate trade – for example, by providing assurances to customers in one country about the quality and safety of products from another country.

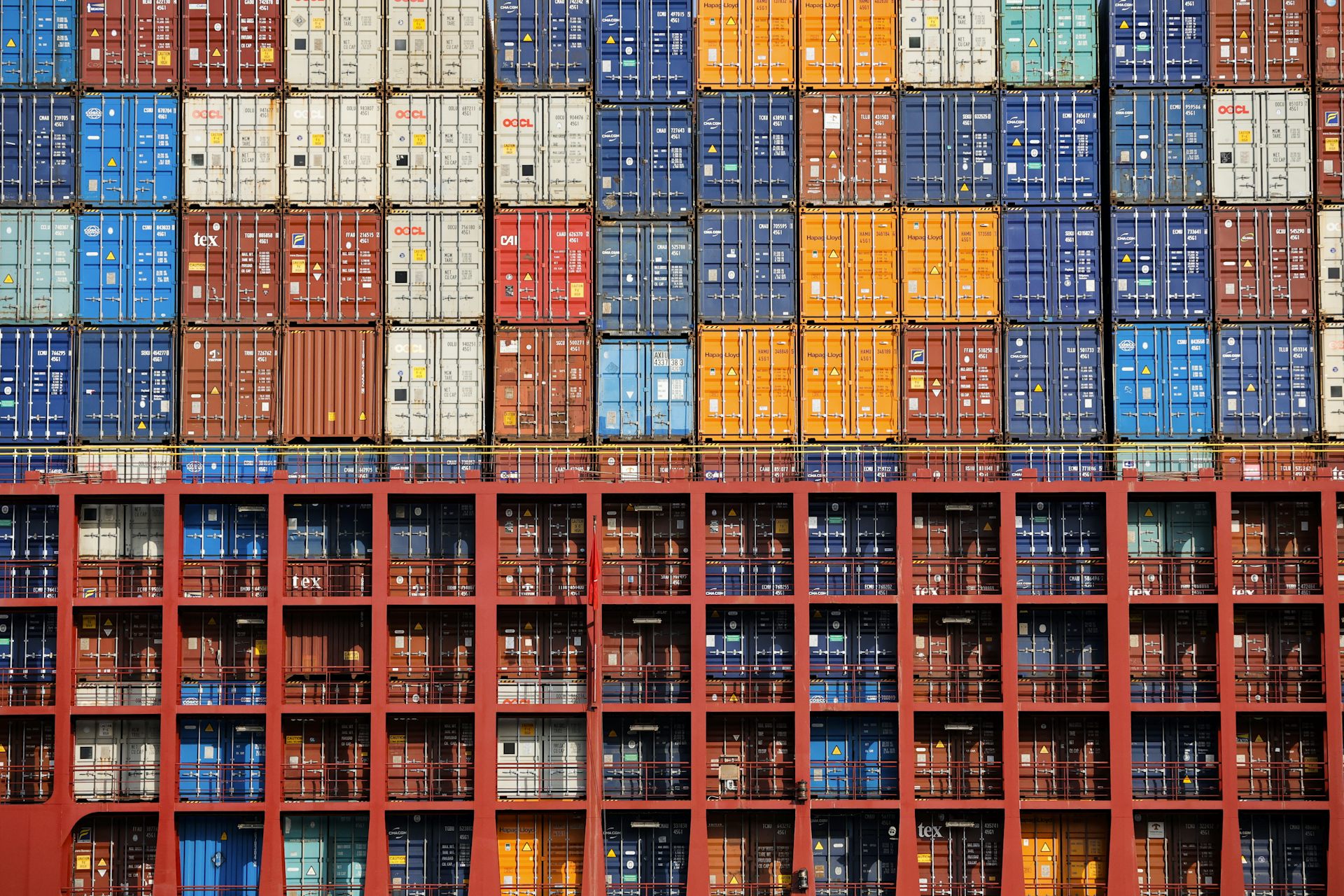

Bienvenido Velasco/Shutterstock

What did the research say?

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) defines a non-tariff barrier as

However, the difficulty is how to achieve this – especially as what is often seen as justified by an importer may be the seen as the opposite or unjustified by an exporter.

ABARES use a broader definition of “non-tariff measures”. This circumvents the tricky problem of trying to ascertain whether a non-tariff measure is justified or unjustified.

As noted by DFAT, enshrined in the rules of the World Trade Organization is the fact that all nations have the right to set trade rules to ensure the health, safety and wellbeing of their citizens and to protect animal and plant health. Australia makes full use of these measures.

any kind of “red tape” or policy measure, other than tariffs or tariff-rate quotas, that unjustifiably restricts trade.

It cuts both ways

The ABARES report is not able to distinguish between the two. It may be questioned whether it is fair to include justified measures in a calculation of the headline tariff-equivalent measure.

EPA

Non-tariff measures are particularly prevalent in agriculture because of the biological nature of food production and the potential risks to human, animal and plant health.

So when does a measure become a barrier? According to DFAT, this is when they are:

Importing a faulty phone may lead to some losses to consumers. But infected agricultural products could severely disrupt a whole sector or even destroy ecosystems. For example, a large foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in Australia could cost the Australian economy more than A billion over ten years.

The ABARES research highlights that non-tariff measures have proliferated in recent years as overall tariff rates have been declining. It also estimates that these measures have an increasingly negative impact on Australia’s agricultural export volumes.

The ABARES report focuses on the impact of these measures on Australian export trade – but questions can also be raised about the use of them by Australia itself.

Read more:

The next round in the US trade war has the potential to be more damaging for Australia