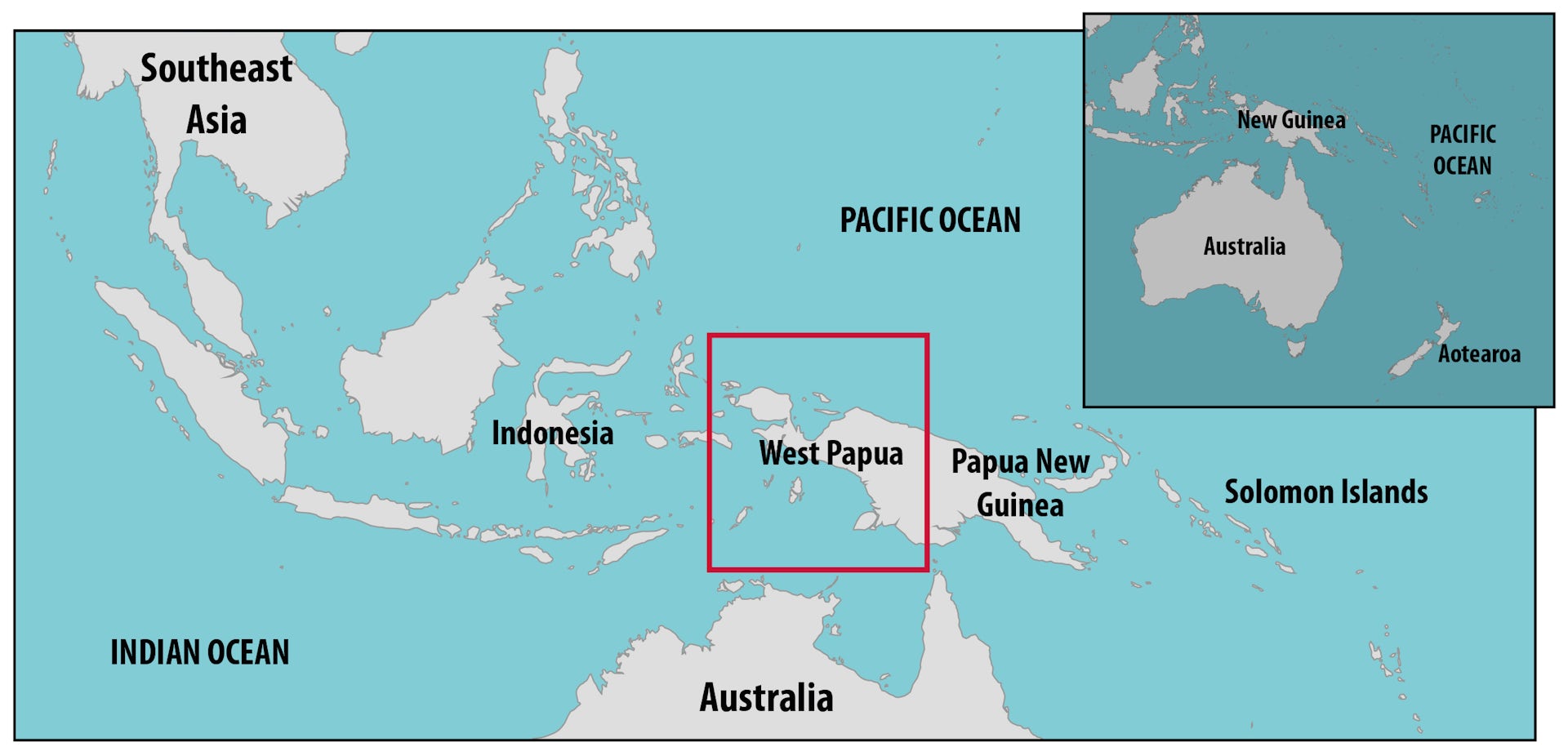

Owing to its violent political history, West Papua’s vibrant human past has long been ignored.

Unlike its neighbour, the independent country of Papua New Guinea, West Papua’s cultural history is poorly understood. But now, for the first time, we have recorded this history in detail, shedding light on 50 millennia of untold stories of social change.

By examining the territory’s archaeology, anthropology and linguistics, our new book fits together the missing puzzle pieces in Australasia’s human history. The book is the first to celebrate West Papua’s deep past, involving authors from West Papua itself, as well as Indonesia, Australasia and beyond.

The new evidence shows West Papua is central to understanding how humans moved from Eurasia into the Australasian region, how they adapted to challenging new environments, independently developed agriculture, exchanged genes and languages, and traded exquisitely crafted objects.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

Early seafaring and adaptation

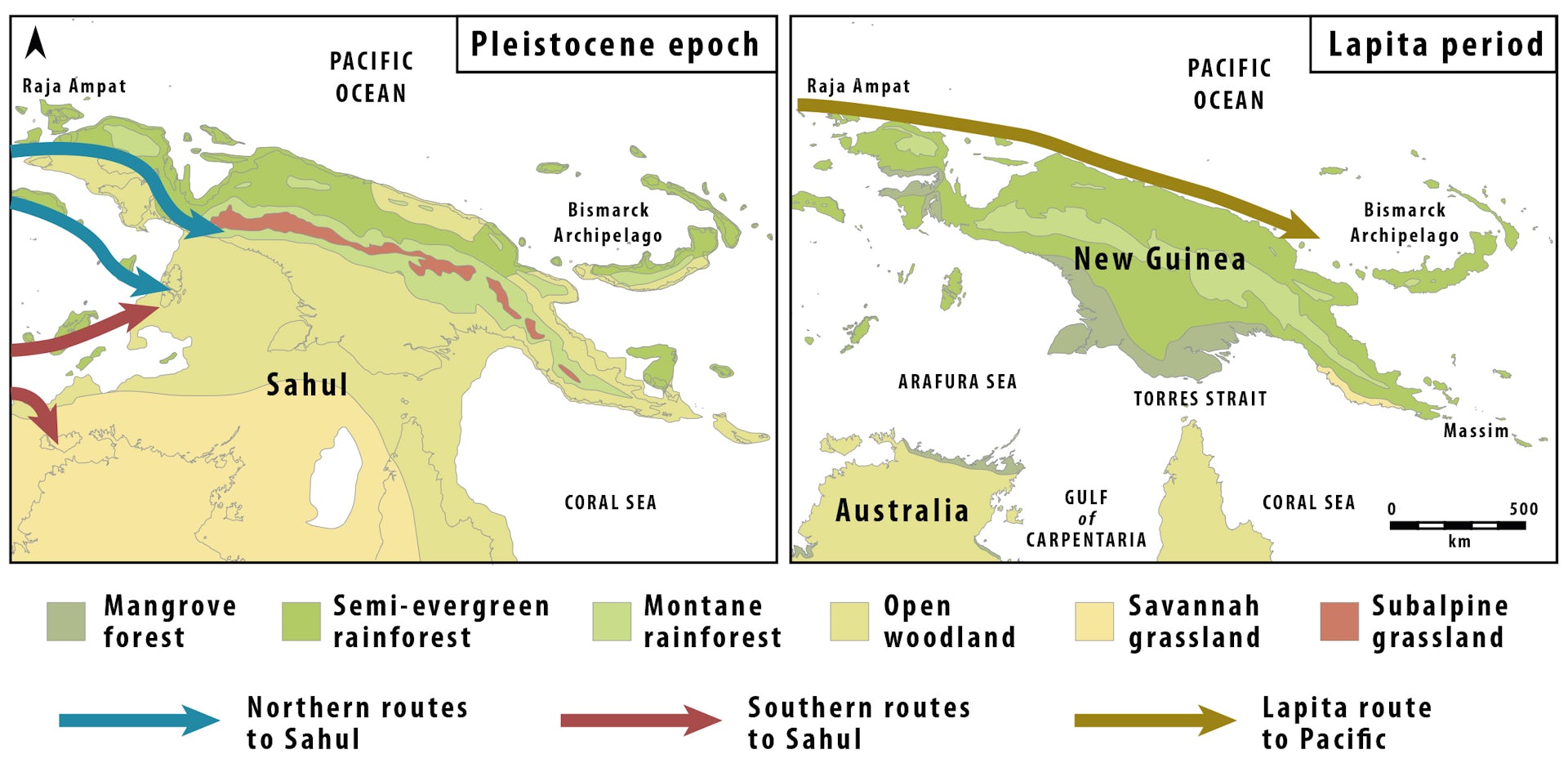

During the Pleistocene epoch (2.5 million to 12,000 years ago), West Papua was connected to Australia in a massive continent called Sahul.

Archaeological evidence from the limestone chamber of Mololo Cave shows some of the first people to settle Sahul arrived on the shores of present-day West Papua. There they quickly adapted to a host of new ecologies.

The precise date of arrival of the first seafaring groups on Sahul is debated. However, a tree resin artefact from Mololo has been radiocarbon dated to show this happened more than 50,000 years ago.

Genetic analyses support this early arrival time to Sahul. Our work suggests these earliest seafarers crossed along the northern route, one of two passages through the Indonesian islands.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

Interestingly, the first migrants carried with them the genetic legacy of intermarriages between our species, Homo sapiens, and the Denisovans, a now extinct species of hominins that lived in eastern Asia. Geneticists currently dispute whether these encounters took place in Southeast Asia, along a northerly or southerly route to Sahul, or even in Sahul itself.

In the same way modern European populations retain about 2% of Neanderthal ancestry, many West Papuans retain about 3% of Denisovan heritage.

As the Earth warmed at the end of the Pleistocene, rising seas split Sahul apart. The large savannah plains that joined West Papua and Papua New Guinea to Australia were submerged around 8,000 years ago. Much of West Papua’s southern and western coastlines became islands.

Social transformations during the past 10,000 years

As environments changed, so did people’s cuisine and culture.

We know from sites in Papua New Guinea that people developed their own agricultural systems between 10,000 and 6,000 years ago, at a similar time to innovations in Asia and the Americas. However, agricultural systems were not universally adopted across the island.

New chemical evidence from human tooth enamel in West Papua shows people retained a wide variety of diets, from fish and shellfish to forest plants and marsupials.

One of the key unanswered questions in West Papua’s history is when cultivation emerged and how it spread into other regions, including Southeast Asia. Taro, bananas, yams and sago were all initially cultivated in New Guinea and have become important staple crops around the world.

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

The arrival of pottery, some 3,000 years ago, represents movements of new people to the Pacific. These are best illustrated by iconic Lapita pottery, recorded by archaeologists from Papua New Guinea all the way to Samoa and Tonga.

Lapita pottery makers spoke Austronesian languages, which became the ancestors of today’s Polynesian languages, including Māori.

New pottery discoveries from Mololo Cave suggest the ancestors of Lapita pottery makers existed somewhere around West Papua. Finding the location of these ancestral Lapita settlements is a major priority for archaeological research in the territory.

Tristan Russell, CC BY-SA

Other evidence for social transformations includes rock paintings and even bronze axes. The latter were imported all the way from mainland Southeast Asia to West Papua around 2,000 years ago. Metal working was not practised in West Papua at this time and chemical analyses show some of these artefacts were made in northern Vietnam.

At all times in the past, people had a rich and complex material culture. But only a small fraction of these objects survive for archaeologists to study, especially in humid tropical conditions.

Dylan Gaffney, CC BY-SA

Living traditions and the movement of objects

From the early 1800s, when West Papua was part of the Dutch East Indies, colonial administrators, scientists and explorers exported tonnes of West Papuan artefacts to European museums. Sometimes the objects were traded or gifted, other times stolen outright.

In the early 1900s, many objects were also burned by missionaries who saw Indigenous material culture as evidence of paganism. The West Papuan objects that now inhabit museums in Europe, America, Australia and New Zealand are connections between modern people and their ancestral traditions.

Sometimes these objects represent people’s direct ancestors. Major work is currently underway to connect West Papuans with these collections and to repatriate some of these objects to museums in West Papua. Unfortunately, funding remains a central issue for these museums.

Many West Papuans continue to produce and use wooden carvings, string bags and shell ornaments. Anthropologists have described how people are actively reconfiguring their material culture, especially given the presence of new synthetic materials and a cash economy.

Klementin Fairyo, Martinus Tekege, Sonya Kawer, Abdul Razak Macap, CC BY-SA

Far from being “ancient” people caught in the stone age – a stereotype propagated in both Indonesian and international media – West Papuans are actively confronting the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

Despite our new findings, West Papua remains an enigma for researchers. It has a land area twice the size of Aotearoa New Zealand, but there are fewer than ten known archaeological sites that have been radiocarbon dated.

By contrast, Aotearoa has thousands of dated sites. This means West Papua is the least well researched part of the Pacific and there is much more work to be done. Crucially, Papuan scholars need to be at the heart of this research.