The key determinants of the strength of the relationship, he says, are communication and policy interaction. If these can continue to be front and centre in 2026, the China-Australia relationship can flourish.

Unsurprisingly, some Chinese scholars we interviewed expressed resentment over Australia’s activities, such as its freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea. In their view, Australia has often become entangled in what Beijing calls American attempts to “contain” its influence.

Unpredictability and instability is on the rise internationally. Given this, Australia and China will need to enhance mutual understanding and keep communication lines open to keep the relationship on track.

These political sensitivities and perceptual differences continue to affect mutual understanding between the two sides.

And despite Albanese’s warn reception in Beijing, political and security concerns continued to complicate the bilateral relationship. This included:

Some Chinese scholars we spoke with pointed out a stable relationship does not necessarily mean a friendly one. One tension point they cited was what they see as Canberra’s efforts to help the United States limit China’s growing regional influence — especially in the Pacific.

There is also a clear recognition in China that Australia is unlikely to turn away from the United States. Wong has been explicit about this: the alliance remains central to Australia’s security, and that of the region.

Yet, Australians ultimately prioritised stable engagement with China over escalating security fears. Attempts to portray China as a threat in the 2025 federal election campaign backfired for then-Liberal leader Peter Dutton and the Coalition.

What happened in 2025?

So, where do things stand now, on the precipice of a new year? To understand what to expect in 2026, we interviewed several scholars in Australia and China.

So, what kind of cooperation can we expect in 2026? Our conversations with Australian and Chinese scholars suggest the relationship will remain stable, with manageable risks. Both sides will feel free to speak their own mind when necessary, while avoiding escalation.

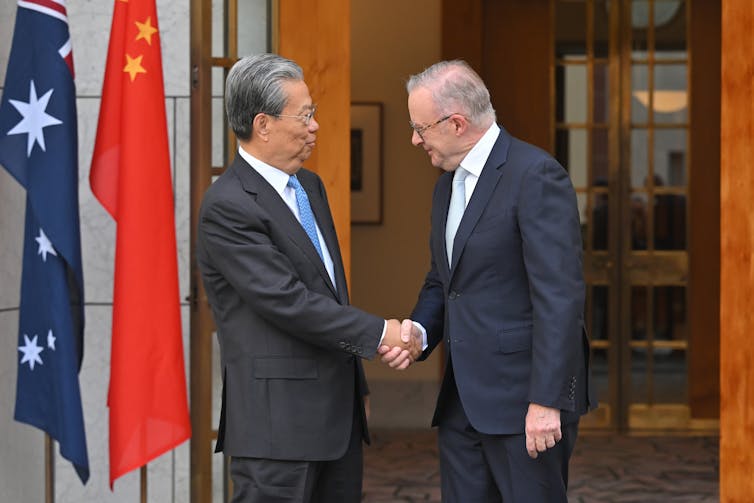

Then, in November, the National People’s Congress chairman, Zhao Leji, visited Canberra. This was the highest-level visit from a Chinese leader since the COVID pandemic outbreak.

allegations of Chinese hackers targeting Australia’s critical infrastructure.

After the election, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese set about solidifying the economic relationship between the two nations by making his second trip to China in July and meeting Chinese leader Xi Jinping in Beijing.

While Canberra avoids the language of “containment”, Chinese commentators often frame Australia as strategically conflicted. It is economically dependent on China, yet politically aligned with the United States.

Rather, this scholar told us, the Albanese government has adopted a more mature approach to managing Australia–China relations. Amid the uncertainty surrounding Trump, Canberra is trying to leverage its central role in the Indo-Pacific region and improve relations with neighbours.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

Differences and tensions persist

There are no rumours of a possible Xi visit to Australia this year. This would no doubt give the relationship an extra boost.

Last year started with a tense moment when a Chinese naval fleet conducted live-fire drills in the Tasman Sea and circumnavigated Australia on the way home. The incident triggered a sharp debate in Canberra about Australia’s maritime security.

Trump’s presidential victory in the US made Australian political leaders and strategic experts even more uneasy.

An Australian scholar we interviewed, however, believes this analysis is overly simplistic.

- However, strategic frictions persist. As another Chinese naval flotilla again headed into the Pacific in December, it was clear wariness remains about China’s military intentions.

- Notably, Albanese also engaged in some “panda diplomacy” by visiting Chengdu’s panda sanctuary – always a sign of goodwill in relations with China.

- Yet, Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s emphasis on what she calls the “four Rs” — region, relationships, rules and resilience — has shown Australia is no longer seeking to be solely reliant on US security.

A new approach

This approach has not gone unnoticed by our Chinese interviewees. During our time in China over the past year, many scholars described Australia’s policies to stabilise relations with China as pragmatic and realistic. They believe Canberra has aligned — at least in part — with China’s interests on trade and cooperation.

However, these positives contrasted sharply with the increasingly tense geostrategic environment.

China’s long-standing opposition to AUKUS

Last year, Australian Treaurer Jim Chalmers brought legal action to try to force the divestment of Chinese capital from strategically critical minerals projects.

When Labor was returned to power in 2022, the China-Australia relationship began to stabilise after what had been a rocky few years.

More fundamentally, the cornerstone of bilateral economic ties – iron ore trade – faced difficulties due to declining Chinese demand and Beijing’s attempted interventions in BHP’s iron ore shipments.

What can we expect in 2026?

As Xu Shaoming, an associate professor in international relations at Sun Yat-sen University, told us, the core of the relationship is still marked by complexity. There’s cooperation in certain areas, competition in others.

Despite criticism from the opposition that he achieved no tangible outcomes, Albanese framed the trip as a success. The two leaders agreed to continue cooperation in a number of areas, including healthcare innovation, green energy, the digital economy and services.

a Chinese fighter jet releasing flares close to an Australian plane in the South China Sea in October, and

Rather, since US President Donald Trump’s return to office, Canberra is pursuing more independent, regionally-led security initiatives.