Along came a spider

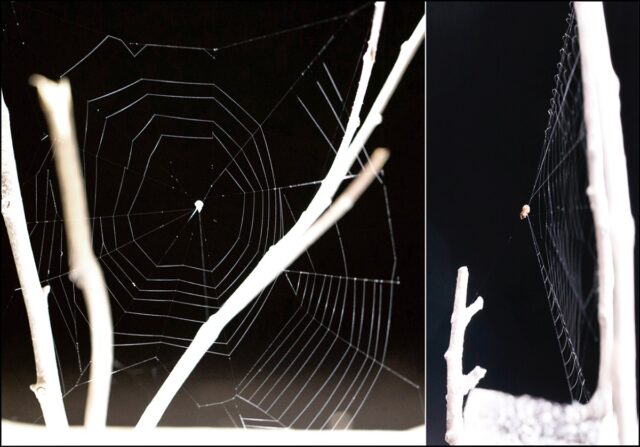

A) Untensed web shown from front view. (B) Tensed web shown from side view.

Credit:

S.I. Han and T.A. Blackledge, 2024

The 19 spiders built 26 webs over the testing period. For the experiments, Han and Blackledge used a weighted tuning fork with frequencies in the mid-range for whirring wings for many mosquito species in North America as a control stimulus. They also attached actual mosquitos to thin strips of black construction paper by dabbing a bit of superglue on their abdomens or hind legs. This ensured the mosquitos could still beat their wings when approaching the webs. The experiments were recorded on high-speed video for analysis.

As expected, spiders released their webs when flapping mosquitoes drew near, but the video footage showed that the releases occurred before the mosquitoes ever touched the web. The spiders released their webs just as frequently when the tuning fork was brandished nearby. It wasn’t likely that they were relying on visual cues because the spiders were centered at the vertex of the web and anchor line, facing away from the cone. Ray spiders also don’t have well-developed eyes. And one spider did not respond to a motionless mosquito held within the capture cone but released its web only when the insect started flapping its wings.

“The decision to release a web is therefore likely based upon vibrational information,” the authors concluded, noting that ray spiders have sound-sensitive hairs on their back legs that could be detecting air currents or sound waves since those legs are typically closest to the cone. Static webs are known to vibrate in response to airborne sounds, so it seems likely that ray spiders can figure out an insect’s approach, its size, or maybe even its behavior before the prey ever makes contact with the web.

As for the web kinematics, Han and Blackledge determined that they can accelerate up to 504 m/s2, reaching speeds as high as 1 m/s, and hence can catch mosquitos in 38 milliseconds or less. Even the speediest mosquitoes might struggle to outrun that.

Journal of Experimental Biology, 2024. DOI: 10.1242/jeb.249237 (About DOIs).