The team lightly swabbed samples from the artifacts’ surfaces and were able to recover human Y-chromosome sequences from several of the samples. Several of these sequences were related and the authors speculate that some might even be Leonardo’s, although they cautioned that the samples would need to be compared to samples taken from the artist’s notebooks, burial site, and family tomb to make a definitive identification. The authors also found DNA from bacteria, fungi, flowers, and animals in some of the samples, as well as traces of viruses and parasites.

DOI: bioRxiv, 2026. 10.64898/2026.01.06.697880 (About DOIs).

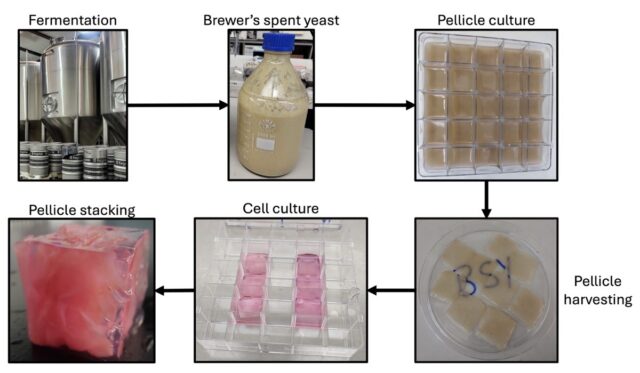

From pint to plate

Credit:

Christian Harrison et al., 2026

Credit:

Christian Harrison et al., 2026

Lab-grown meat is often touted as a more environmentally responsible alternative to the real deal, but carnivorous consumers are often put off by the unappealing mouthfeel and texture (and, for me, a weird oily aftertaste). A new method using spent brewer’s yeast to make edible “scaffolding” for cultivating meat in the lab might one day offer a solution, according to a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition.

Typically, a nutrient broth is used as a source of bacteria for the scaffolding. But Richard Day of University College London and his co-authors decided to use brewer’s yeast, usually discarded as waste, to culture a species of bacteria known for making high-quality cellulose. Then they tested the mechanical and structural properties of that cellulose with a “chewing machine.” They concluded that the cellulose made from spent brewer’s yeast was much closer in texture to real meat than the cellulose scaffolding made from a nutrient broth. The next step is to incorporate fat and muscle cells into the cellulose, as well as testing yeast from different kinds of beer.

DOI: Frontiers in Nutrition, 2026. 10.3389/fnut.2025.1656960 (About DOIs).

Water-driven gears

New York University scientists created a gear mechanism that relies on water to generate movement. For some conditions, the rotors spin in the same direction like pulleys looped together with a belt.

Gears have been around for thousands of years; the Chinese were using them in two-wheeled chariots as far back as 3000 BCE, and they are a mainstay in windmills, clocks, and the famed Antikythera mechanism. Roboticists also use gears in their inventions, but whether they are made of wood, metal or plastic, such gears tend to be inflexible and hence more prone to breakage. That’s why New York University mathematician Leif Reistroph and colleagues decided to see if flowing air or water could be used to rotate robotic structures.